WHERE BOOKS LIVE WELL

It could once be said that the quickest we to be rid of the strain and bustle of teeming Bombay was to abandon land for a soothing cruise in the harbour. But in a city not short on ambient richness there are alternative havens, like some of BOMBAY’S SECLUDED LIBRARIES. Almost without exception these offer cool shelter and quiet and FOY NISSEN finds that the outstanding examples prove to have been 19th century foundations…

The approach to the library of the Asiatic Society of Bombay, at the eastern end of Horniman Circle is unmatched elsewhere in the city. From street level one walks up an expansively wide, theatrical incline of dazzling steps to the main pedimented portico with its eight Doric columns. Here on these steps in the cool of the evening after dark, less privileged students may be seen during examination-time, swotting for the ordeal to come. They read either by street-light or under a thoughtfully provided flood-lamp. This tableau alone is one of the institutions in character with the city.

The main entrance leads to what is now the reading hall of the incorporated Central Library section of the complex. Initiates and Members make for the northern porte-cochere which draws one through a curtain of sudden darkness towards Matthew Noble’s brilliantly spotlit 1865 statue of Jagannath Shankarset in the staircase well. Shankarset was a benefactor of both the Asiatic Society and of the city. From here one reaches the lobby level up an exquisitely curved, divided Regency staircase.

The lobby is peopled mostly with the marble statuary by distinguished Victorian sculptors. Dramatically lit under another skylight, Francis Chantrey’s 1836 statue of Governor Sir John Malcolm commands the vestibule. In a corner alcove stands Thomas Woolner’s sympathyetic 1872 portrait figure of Sir Bartle Frere, no mean Indian linguist himself and, when Governor, the entrepreneur of Bombay’s High Victorian public architecture. Across the stairwell presides a monumental likeness of India’s first baronet, Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy, fashioned by the sculptor Baron Carlo Marochetti. Portraits in oils hang on the wall at each side, one of Dr. Bhau Daji Lad, the other of Pandit Bhagwanlal Indraji, both of them distinguished Members of the Society in their day.

A charming miniature portrait in the stairwell passageway depicts Maneckjee Cursetjee, who in 1840 was the first Indian to have been elected a Member of the Asiatic Society. A fourth portrait commemorates the Society’s founder-President, Sir James Mackintosh, who was then the Recorder of Bombay and head of the Judiciary. Mackintosh and sixteen luminaries interested “in promoting useful knowledge particularly such as was more immediately connected with India”, met at Government House, Parel, on 26 November, 1804, to form the Literary Society of Bombay.

Also present were William Erskine, the first Honorary Secretary, who was a Magistrate and Master of Equity, and was later to become the provost of St Andrew’s; Jonathan Duncan, then Governor of Bombay and an influential supporter of the fledgling Society.

It is interesting to note that one of the founder-members, along with George Annesley, Viscount Valentia, was the artist Henry Salt, whose topographical view of India are much prized today. Other founder-members included Captain Edward Moor later to attain best-seller fame as the author of The Hindu Pantheon – as well as Col. Joseph Boden, who was to endow the celebrated Chair of Sanskrit at Oxford University.

In 1805, the Literary Society enlarged its scope by acquiring the Medical and Literary Library of Bombay, a private institution founded in 1789. By January 1830, the Society changed its name, for affiliation convenience, to the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. This differentiated it from the illustrious Calcutta Branch founded earlier. It was Governor Sir John Malcolm who arranged that the Society should enjoy a permanent right to its share of the new Town Hall premises from November 1830. After 1947 the Society simplified its name to become the Asiatic Society of Bombay.

Space in the vestibule not reserved for Augustan Statuary or card-catalogue cabinets is taken up by some elegant teak and leather-upholstered settees. You may be excused if you discern a flicker of life here, as Fellows of the Society and Library members indulge in comfort and earnest concourse. You may also be pardoned if the heady interior twilight and exquisite Regency spaciousness reminds you of a superior London club or even of the inner precincts of an Oxbridge college. You are in one of the oldest intellectual power-houses of Bombay.

The booksy mustiness inside is real, a compost of old teakwood and camphor shelves, spiral wooden stairways to elevated galleries and wall-spaces covered completely with books. A vintage

art-deco etched-glass-shaded table lamp catches one’s on the Assistant Librarian’s desk. The dedication of the staff is professional. From the hand-crafting bookbinders in the bindery to the team of expert librarians. At an “optimum leaning-height” issues counter, staff “ know the members as individuals” and library-tickets and identity cards are disdained.

High floor-to-cornice level windows let in some sunlight and provide much sought after cool and breezy reader’s retreats. No diffidence need be felt when discerning a library member slouched in sleep in one of these niches. The Periodicals Reading Room indeed offers superior inducements to court somnolence, easy-chairs here have matching foot-stools to facilitate partial levitation.

It would be a mistake to assume that soporific vapours alone rule over the Asiatic Library. Its book-stock is a bibliophile’s delight and the envy of every library in Asia. Its research are formidable and include complete runs of several early Bombay newspapers and journals, 2000 oriental manuscripts, a galaxy of rare editions and some 10,000 Indian coins. Perhaps the most valuable asset of this institution is its world-wide intellectual prestige and the cachet of being an invited contributor to the learned Journal of The Asiatic Society of Bombay, which has been published since 1841.

One of the most attractive late Victorian buildings in Bombay is the

J N Petit Institute, a sturdily-plated yet delicately flowering neo-Gothic structure at the busy Dr. Dadajee Naorojee and Sir Pherozshah Mehta crossroads. Its double-storey high, pointed arch windows and slender red sandstone columns make it instantly recognisable. Few would guess that its present form dates from 1938 when the original 1898 structure was raised a storey and extended.

The administration and accessible book-stacks are housed on the original first floor where 19th century cast-iron columns, with custom-made monogrammed brackets support a gallery enlivened with a delicately curved iron balustrade. A spacious westerly Research Room houses several unusual and surprising novel volumes, such as kirtikar’s The poisonous snakes of Bombay, or the curious Kaisarnama-ki-Hind, a poem in Persian dedicated to the British Queen Empress in 1877, illustrated with beautifully produced contemporary photographic prints.

On the second floor, the pride of the building is its end-to-end obstruction free Reading Room. The original long, green, marble-topped tables here accommodate some 450 busy readers of all ages who represent the popular pulse of this Institution.

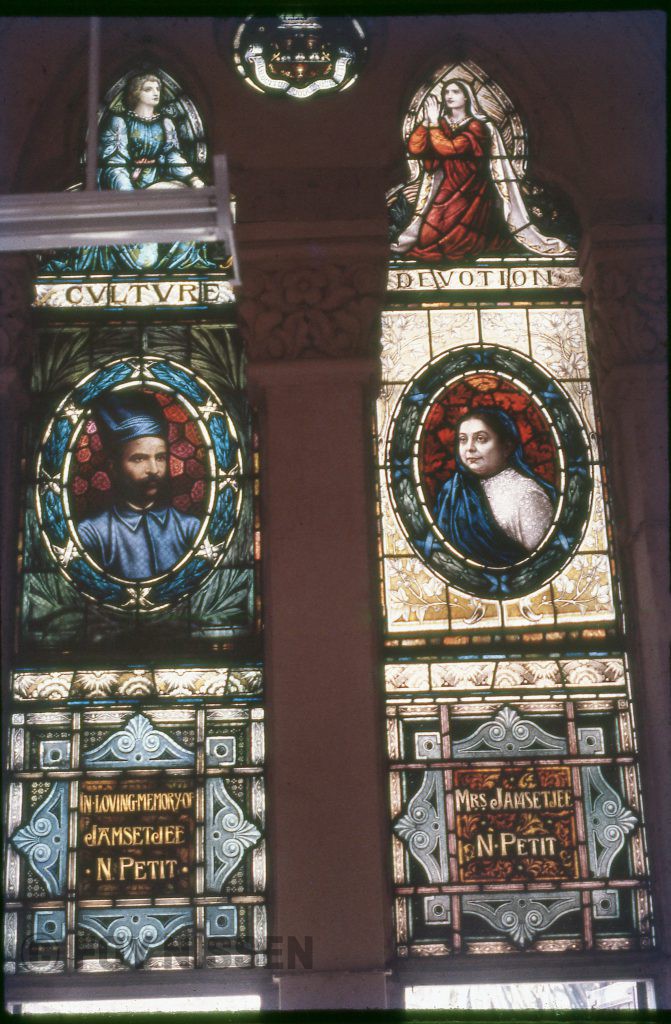

The north-facing Reading Room alcove glows with the rich colours of its stained glass windows. These beautifully executed portraits honour the memory of Nasserwanji Maneckjee Petit, Bai Dinabai Petit and their family, the major benefactors of the library after its small beginning in 1856 when it was started as a private mutual leading library by a coterie of young Parsi students. Each stained-glass portrait is adorned with a legend proselytising Victorain ideals held in high esteem – Courtesy, Generosity, Commerce, Charity, Culture and Devotion.

The origins of the David Sassoon Library encompass all these ideals and more, being an amalgam of interests representing the Victorian reverence for new technology and the evangelism of Empire commerce. It was founded as a library in 1847 by the foremen mechanics of the Government Dockyard and Mint and called the Bombay Mechanics’ Institute. In 1873 the present building was completed thanks to a donation from Sir David Sassoon and the Institute was renamed The David Sassoon Library and Reading Room.

This architectural gem, opposite the Jehangir Art Gallery complex, is easily Bombay’s most felicitous small-scale neo-Gothicism, combining grace in its proportions with imagination in its polychromatic use of local materials. The flooring still blazes with the rich colours of its original Minton tiling.

The Sassoon Library caters to general tastes and exercises an unabashed bias for fiction. Yet it asserts an individuality that is little short of the eccentric. It has never closed: its doors have remained open to its members from 8 am to 9 pm every day for over a century. Its 19th century clock still runs on its pendulum weights devotedly maintained by the longest serving peon, Mr. Patil. Its teakwood counter has literally changed sides across the road, for it was once the bar at The Wayside Inn. In the stairwell Thomas Woolner’s statue of David Sassoon greets you with Messianic earnestness and as you hurry past upstairs to the stacks of fiction and periodicals, a marble bust of James Berkeley surveys you from an arched window niche at mezzanine level. An almost bizarre preoccupation with comfort distinguishes the arcaded first floor verandah which ventilates the Reading Room. Here some twenty planters’ chairs are ranged, facing west. When in use they often conspire to convert this area into a dormitory.

The Sassoon Library’s most precious asset owes its existence to a common malady – shortage of funds. Striking at the critical building stage in the last century, this mercifully deprived the project of a planned lecture-hall that would have doubled the floor space area. How fortunate that instead, today, the elegant Gothic façade screens an unsuspected and incomparable restful garden retreat for members on the western side. Whereas the eastern verandah retains light deflected through its arches across the interior stone-work, the garden area is enlivened with birdsong amidst a skein of overhead shade from a mixture of Royal Palms, chickoo and mango, jackfruit and almond and gul mohur trees, and from the Ashoke, Amla and white Jasmine.

Just two blocks away, the city’s most sophisticated Gothic symbol stands 280 feet high. This is the Rajabi Clock tower surmounting Bombay University’s Library and Reading Room. Designed by

Sir C G Scott and completed in 1874 it commemorates the donor Premchand Roychand’s mother. Once the tallest building in Bombay, no latter-day sky-scraper can match its dignified tranquillity at a distance nor its external finish at close quarters. Local stone masons carved its exquisite, Indianised Gothic ornamentation.

Not surprisingly the University Library preserves a rich collection of reference works, research material, several important manuscript collections in Persian, Arabic, Sanskrit and Marathi and a valuable selection of early Indian imprints.

Gothic architectural luxury was also lavished on the Library interior and its first floor Reading Room must be the most congenial space for such use in the city. Students and scholars work at long teakwood tables that were part of the original design under a soaring vaulted teakwood roof. Arcaded stone verandahs which straddle the north-south orientation of the building along its western side act as conduits for fresh sea breezes drawn off the sea nearby. Superlative stained glass windows colour the vast Reading Room at each end, helping for filter light, relax the eye and complete this Victorian domestication of Indian education and research. Indeed the only comparable ambience created to this end may be enjoyed in the Reading Hall at St. Xavier’s College. For all its low, horizontal emphasis on scholarly tranquillity however, it lacks the spacious élan of the University’s magnificent gift to scholarship.