PRIDE OF PLACE

As Bombay embraces the age of ever-accelerating change, it’s graceful architecture, perhaps one of the most eloquent expressions of an era, fades silently away.

Foy Nissen dwells wistfully on these vanishing facades.

BOMBAY’S 19th Century public architecture is renowned for its Victorian hallmarks. A chain of neo-Gothic buildings straddles south Bombay resplendently, symbolising civic and official enterprise in the idiom of its time. It provided the city with a distinguished formal grandeur, distancing the humanity of prevalent housing norms from the formality of the Raj and from the amour-propre of commercial progress.

This neo-Gothic sprawl, the ‘diagram of Victorianism’ which 19th Century British officialdom etched onto the Fort area, was planned to accommodate people attending government officers, hospitals, courts, centres of education or using railway systems. Today most of the buildings continue to be used as before but their contemporary domestic neighbours have begun to display characteristics of an endangered species. If these early domestic houses disappear altogether we may become the poorer for losing the templates for an alternative mode of living.

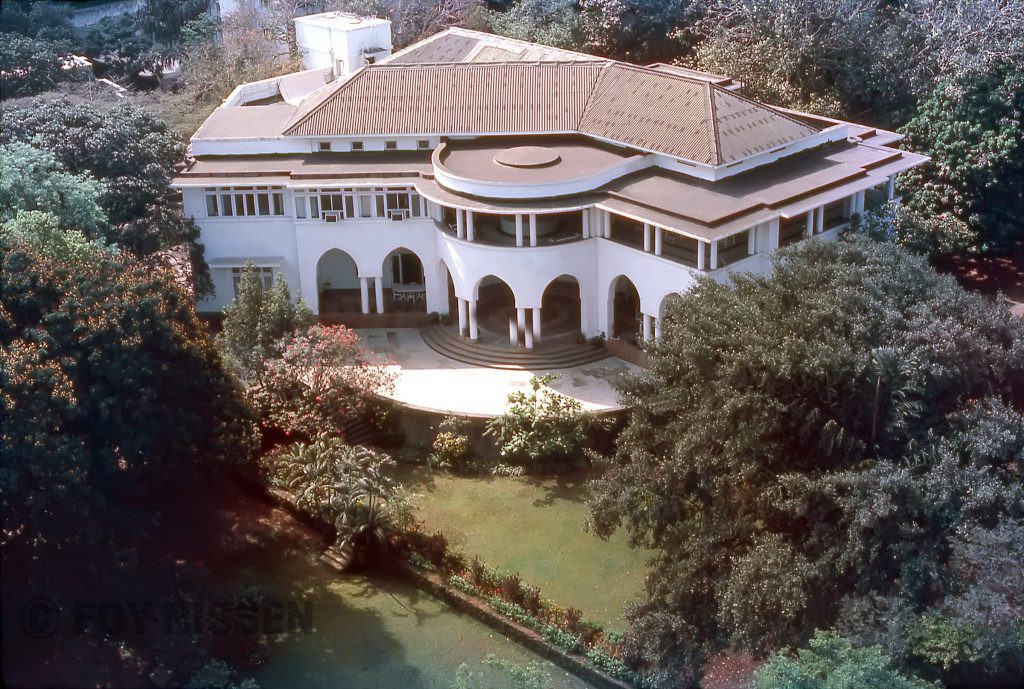

A few survivors – detached villas and bungalows – can be seen now on Malabar Hill, Cumballa Hill, at Breach Candy or in precincts like Kotachiwadi, Matharpacady and suburbs such as Bandra. Some of these residential areas still tenuously retain pre-industrial patterns of land-use.

Elsewhere in the city pressures of growth and land-hunger, along with technological changes and consequent cost adjustments, have combined to oust the old domestic building tradition which offered wider choices perhaps for individual expression. Modern apartment-block living in Bombay limits the possibilities almost exclusively to individual efforts directed at the decoration of interiors, perhaps, mercifully. There is an admissible margin of caution both ways. James Douglas, who loved Bombay and its history, could not have been more accurate when, writing in 1893, he remarked that, “if every man is to be permitted to erect anything he pleases, then we may bid adieu to the inheritance of beauty that has come down to us in Malabar Hill, blessed with the poetry of nature, but deficient in the poetry of art.”

Separate housing units were the norm, understandably, at this earlier stage, as a 19th Century topographic over view of Breach Candy makes clear. “The whole locality”, according to W J Adam’s descriptive High Victorian survival-kit, “is densely studded with handsome Bangalas (Bungalows) delightfully situated in romantically arranged compounds (gardens) commanding an extensive marine view.”

Today we can see few of these ‘romantically arranged compounds’ in Bombay; though the tradition is maintained at the Municipal Commissioner’s Bungalow or in the delightful formal garden frontage – it was the location venue for the garden-party scene in Attenborough’s film, ‘Gandhi’ – at ‘Bombarci’ on Cumballa Hill. Until a few years ago the downhill sweep of terraced gardens provided a sensitively landscaped setting for Jinnah House, the chaste, historic Art-Deco villa designed by Claude Batley.

Deprived of their original ambience, these old domestic buildings now speak to us in a different way. Endearing details, once taken for granted, reveal themselves anew like the very concepts, bungalow or verandah, which have long asserted universal rights as settlers and colonisers, but whose meaning sharpens the way in which we understand living-space today.

On a tour round Bombay, the presence of a grand villa built on a promontory or on rising ground can still catch the eye. Perhaps the most imposing mansion, ‘Mount Nepean’, with its balustraded driveway winding uphill was once typical, today unique. If one is close enough one can notice the elegant extravagance of an open-air divided marble stairway leading to the parterre terrace. ‘Mount Nepean’ is also rich in the neo-classical marble statuary which serves to define the sight-lines within a landscaped vista. The days when one could enjoy a type of landscaped folly – an orchestration of statuesque marble figures used to decorate many a Bombay garden – are now consigned to memory.

An architectural feature which ‘Mount Nepean’ shares with turn-of-the-century housing all over the city is the use of stained-glass to soften the infusion of daylight indoors. These polychrome, patterned windowpanes and fan-lights come alive on balconies and in windows at night A set of stained-glass lights for the main staircase at ‘Mount Nepean’ is culturally evocative and representative. Each window enshrines a neo-classical image of one of the Muses. They symbolise Science, Poetry and Music and, this being Bombay, it will come as no surprise to know that ‘music’ is shown playing a violin.

An essential component of a bungalow is its verandah, a protective device which helps to cool interiors. It also affords a pleasant, sheltered platform for socialising or for carrying out household chores. The verandahs of the grand villas of Bombay focus vistas across cool marble floors and through neo-Gothic arches and columns. A great deal of good taste and skill was lavished on their component proportions, choice of stone and sculpted decoration. An entrance verandah will often centre on a porte-cochere. In the suburb of Bandra the hill-side presents a separate plane of attention, providing us with several opportunities to admire the Italian Renaissance flourishes with which sweeping marble stairways proclaim the presence of their villas attached above.

A counterpart to verandahs is the balcony, and a look round the nineteenth and early twentieth century street facades of Bombay makes it quite clear how important a balcony must be for those fortunate enough to enjoy such a facility. The more so when it affords a view of a patch of sky – a cosmic holograph which satisfies an important psychic need. Bombay’s balconies display a rich decorative variety, remarkable for graceful form, stained-glass light-filtering and attractive detailing. There is vintage industrial design in the many cast-iron brackets and balusters which also act as filters for delicate patterns of light and shade. Many of the older wooden-frame buildings preserve the western Indian tradition of carved wooden balcony components and cornices. These can be seen in streets in the Fort bazaar, or in several precincts like Girgaum, Bhuleshwar, Null Bazaar and Pydhonie.

Of equal visual merit are the streamlined balconies of the Art-Deco era, predominantly along Queen’s Road, Cuffe Parade and Marine Drive. The plastic sweep of their moulded planes is often enlivened with elegant contemporary ironwork, irreplaceable today as are the matching ironwork window grilles. Cast-iron was a Victorian building totem par excellence and the benevolent Queen could be said, in her lifetime, to have been on the verge of assimilation into the Indian pantheon as a mother-goddess. Many of Bombay’s cast-iron balcony balustrades are decorated with profile medallions of Queen Victoria, whilst others – more narrowly customer-specific – are adorned with Zoroastrain sun-symbols. When looking at some of these Victorian houses do not miss the delightful cast-iron staircase risers, which despite their subordinate status, make such a delicate filigree of the light.

For all the disadvantages that some of these old houses may now harbour, their impact visually imposes a striking sense of order. This derives from traditions of building design which ensured cohesion in their group scale. In turn this was based partly on dimensions evolved out of hand-made detailing in woodwork, moulding and roof tiling, in modules geared to time-tested material solutions to the requirements of convenient daily use. The coping of a curved garden wall in a precinct like Kotachiwadi is both functional and aesthetically satisfying, manifestly part of an integrated response to human living needs that modern commodity builders recklessly ignore. Nor was concern for human needs divorced from the old-time building craftsman and designer’s concern for materials and how they might be used. Notice the way that an anchoring wooden baluster for a stairway that opens onto the street in Kotachiwadi is given protection with a specifically designed stone base.

This is a seemingly insignificant detail which expresses the successful street-level interpenetration and intimacy – nevertheless ensuring privacy inside – which is so characteristic of the building style preserved in these areas. It is also salutary to realise that these housing units are rooted in traditions which were evolved in rural garden suburbs, but which have asserted their adaptability to the conditions of an alien modern environment. The deceptively self-imposed, tranquil pedestrianisation of these streets and by-lanes would be the envy of advanced city planners abroad. Here in Bombay it is time that these advantages are given statutory life through enlightened legislation. Whilst they are still with us, meanwhile, the small-scale vintage houses in Bandra, in Matharpacady and Kotachiwadi, along with some of the grand Victorian mansions remind us of a shared concern for an ordered living pattern. The needs which their architectural features satisfy confront us with the possibility of alternative algorithms to apply to problems of urban planning and building design.